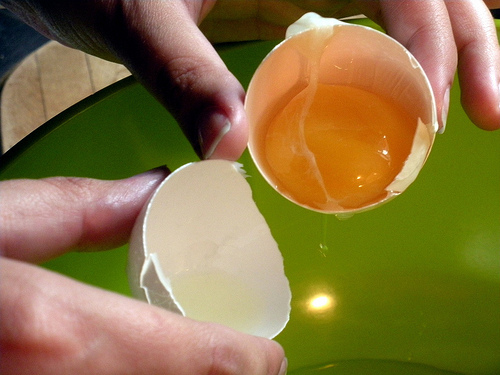

In my last entry I introduced shell theory as pertaining to masonry domes. The essential aspects of this theory include a thin-walled, doubly curved structure. “Thin walled” is not exceeding one tenth of the radius of the arch or dome.

Much work has been done on Finite Element Analysis of domes and arches. A couple good examples of research which include literature surveys of this topic include “Limit state analysis of hemispherical domes with finite friction” (D. D'Ayala and C. Casapulla) and “Structural Assessment of Guastavino Domes” (H.S. Atamturkur). These two academic papers provide a rather complete analysis of FEA methods used by the authors and include a decent look at research by others in the field.

As I stated before, FEA is –in my view- an imperfect method for analyzing masonry domes. I find Thrust Line Analysis to be a more insightful approach to understanding the forces, stresses, strains, and failure mechanisms within masonry domes. The visual representation of thrust lines within shell thickness gives a direct representation of stress within the wall thickness, whereas FEA typically use different shades of color for different stress levels over the entire dome. Excellent work on thrust line analysis in masonry domes has been done by Philippe Block, Thierry Ciblac and John Ochsendorf at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as described in their paper “Real-time limit analysis of vaulted masonrybuildings.”

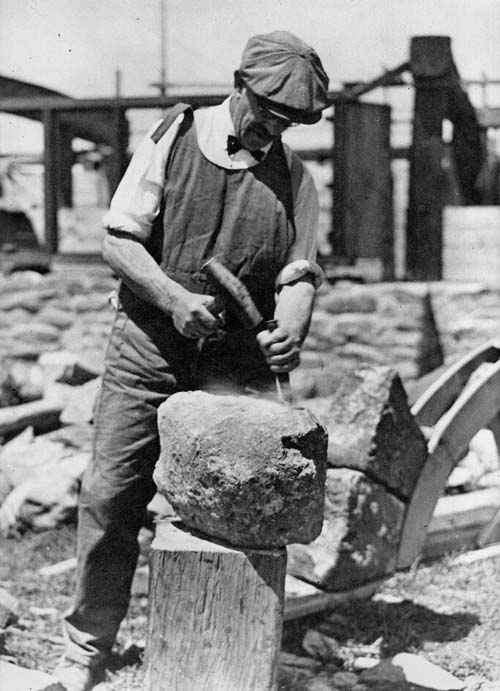

A thrust line is a visual representation of the force present in a given block or voussoir within an arch. If the thrust line is kept within the wall thickness, then the structure is stable and will remain intact (as shown below). If the thrust line leaves the wall thickness or even touches the wall boundary, then a hinge is created, the structure can buckle and fail or collapse (as shown above).

A masonry shell is strongest if the thrust line is kept at the center of the wall thickness. The masonry unit, or voussoir, or block is strongest and best able to bear its load if the thrust line is in the middle of the block.

If an individual block moves or slides out of the shell’s curved plane, then the thrust line will be closer to the inside of the block. This can create a hinge if the thrust line touches the inner surface of the block, possibly resulting in failure and collapse of the dome or arch. It is critical to keep individual masonry units in the curved surface of the shell.

The symmetry of the dual inverse mirror plane (dimp) blocks as discussed in this blog creates an interlocking feature which prevents blocks from moving outside of the curved shell surface. Blocks are effectively locked into the tangential plane of an assembled spherical section.

This symmetry also creates a “line-of-sight” exactly in the middle of the block, halfway between the inside and outside of a dome. This line of sight allows for a wire, or cable, or other tensile element to be woven between adjacent blocks. This geodesic tensile web within the center of a masonry shell (feature 660 below) serves the purpose of keeping blocks located within the tangential plane of the dome, arch, etc.

Shell theory in a masonry dome analyzes deflection of the shell surface under various loading conditions. Deflection or movement of the shell weakens the shell because the thrust lines can then reach the inner and outer surface of the masonry wall, resulting in a hinge being created; failure and collapse.

Since the “dimp” blocks are configured with key and keyway symmetry; together with the line-of-sight at the center of the abutting edge of each block which allows a woven tensile element, all blocks are effectively prevented from deflecting or moving outside of the tangential curved surface of the masonry shell. If the blocks cannot move out of the shell, they are much less prone to failure or collapse.

Much work has been done on Finite Element Analysis of domes and arches. A couple good examples of research which include literature surveys of this topic include “Limit state analysis of hemispherical domes with finite friction” (D. D'Ayala and C. Casapulla) and “Structural Assessment of Guastavino Domes” (H.S. Atamturkur). These two academic papers provide a rather complete analysis of FEA methods used by the authors and include a decent look at research by others in the field.

As I stated before, FEA is –in my view- an imperfect method for analyzing masonry domes. I find Thrust Line Analysis to be a more insightful approach to understanding the forces, stresses, strains, and failure mechanisms within masonry domes. The visual representation of thrust lines within shell thickness gives a direct representation of stress within the wall thickness, whereas FEA typically use different shades of color for different stress levels over the entire dome. Excellent work on thrust line analysis in masonry domes has been done by Philippe Block, Thierry Ciblac and John Ochsendorf at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as described in their paper “Real-time limit analysis of vaulted masonrybuildings.”

A thrust line is a visual representation of the force present in a given block or voussoir within an arch. If the thrust line is kept within the wall thickness, then the structure is stable and will remain intact (as shown below). If the thrust line leaves the wall thickness or even touches the wall boundary, then a hinge is created, the structure can buckle and fail or collapse (as shown above).

A masonry shell is strongest if the thrust line is kept at the center of the wall thickness. The masonry unit, or voussoir, or block is strongest and best able to bear its load if the thrust line is in the middle of the block.

If an individual block moves or slides out of the shell’s curved plane, then the thrust line will be closer to the inside of the block. This can create a hinge if the thrust line touches the inner surface of the block, possibly resulting in failure and collapse of the dome or arch. It is critical to keep individual masonry units in the curved surface of the shell.

The symmetry of the dual inverse mirror plane (dimp) blocks as discussed in this blog creates an interlocking feature which prevents blocks from moving outside of the curved shell surface. Blocks are effectively locked into the tangential plane of an assembled spherical section.

This symmetry also creates a “line-of-sight” exactly in the middle of the block, halfway between the inside and outside of a dome. This line of sight allows for a wire, or cable, or other tensile element to be woven between adjacent blocks. This geodesic tensile web within the center of a masonry shell (feature 660 below) serves the purpose of keeping blocks located within the tangential plane of the dome, arch, etc.

Shell theory in a masonry dome analyzes deflection of the shell surface under various loading conditions. Deflection or movement of the shell weakens the shell because the thrust lines can then reach the inner and outer surface of the masonry wall, resulting in a hinge being created; failure and collapse.

Since the “dimp” blocks are configured with key and keyway symmetry; together with the line-of-sight at the center of the abutting edge of each block which allows a woven tensile element, all blocks are effectively prevented from deflecting or moving outside of the tangential curved surface of the masonry shell. If the blocks cannot move out of the shell, they are much less prone to failure or collapse.